How George Lucas used an ancient technique called “ring composition” to reach a level of storytelling sophistication in his six-part saga that is unprecedented in cinema history.

By Mike Klimo

The interesting thing about Star Wars—and I didn’t ever really push this very far, because it’s not really that important—but there’s a lot going on there that most people haven’t come to grips with yet. But when they do, they will find it’s a much more intricately made clock than most people would imagine.

—George Lucas, Vanity Fair, February 2005

The famous yellow letters of the opening text crawl slowly recede into the vastness of space. The camera pans down to reveal a large planet and its two moons. Suddenly, a tiny Rebel ship flies overhead, pursued, a few moments later, by an Imperial Star Destroyer—an impossibly large ship that nearly fills the frame as it goes on and on seemingly forever. The effect is visceral and exhilarating.

What’s more, the single continuous shot (it lasts about 30 seconds) illustrates both the film’s basic storyline, a small band of Rebels fight an evil galactic empire against overwhelming odds, and one of its central themes, the indomitable nature of the human spirit—all without uttering a single line of dialogue. It’s a masterful example of visual storytelling.

This is, of course, the opening of Star Wars: Episode IV—A New Hope (1977), arguably one of the most famous opening shots in cinema history, and rightfully so.

Now compare this to the opening of Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace (1999): The signature opening title crawl slowly disappears into infinity, we pan down, a small spaceship travels quickly past the camera, and then … lands.

The man behind Red Letter Media’s enormously popular video reviews of the prequel trilogy, Mike Stoklasa, probably summed up the feelings that many Star Wars fans had when they saw this for the first time, particularly those who’d waited 16 long years, since 1983’s Star Wars: Episode VI—Return of the Jedi, for Menace: “From the very start of [The Phantom Menace] I could tell something was really wrong just by the way it started. It opens with some boring pilot asking for permission to land on a ship that looks like a half-eaten donut, with a donut hole in the middle.” 1

Admittedly, the seemingly bland and uninspired opening of Menace doesn’t pack quite the same punch as A New Hope’s and instead leaves one feeling a little underwhelmed, to say the least. The problem, though, is that it may not be the fairest of comparisons. Because something really interesting happens when you compare Menace’s opening to that of Return of the Jedi’s.

In Menace, a Republic space cruiser flies through space towards the planet Naboo, which is surrounded by Trade Federation Battleships. Cut to inside the ship’s cockpit. The captain requests permission to board. On the viewscreen, an alien gives the okay. The space cruiser then flies towards a battleship and lands in a large docking bay.

In the opening of Jedi, an Imperial Shuttle exits the main bay of a Star Destroyer and flies towards the Death Star, which looms over the forest moon of Endor. Cut to inside the shuttle’s cockpit. The captain requests deactivation of the security shield in order to land aboard the Death Star. Inside the Death Star control room, a controller gives the captain clearance to proceed. The shuttle then flies towards the Death Star and lands in a large docking bay.

Here’s a side-by-side comparison of the two openings:

As you can see, there are some definite similarities between the two sequences. They both consist of a small ship landing on a spherical battle station that’s orbiting a lush, green planet. And they both consist of a similar series of shots.

But, at the same time, there are some clear differences between the sequences. First off, in Menace, the Republic cruiser is a “good guys” ship. In Jedi, the Imperial Shuttle is a “bad guys” ship. Second, outside the cruiser’s cockpit window we see the peaceful planet of Naboo whereas outside the shuttle’s window we see the partially constructed skull-like Death Star. Third, the screen direction is reversed. The Republic cruiser moves across the frame from left to right, the Imperial shuttle moves right to left. Even some of the camera angles are reversed in a way. The cruiser enters the docking bay in a low-angle shot, the shuttle in a high-angle shot. From this standpoint, then, the two sequences seem almost like mirror images of each other.

Now, the prequels are filled with frequent callbacks to the original films, to be sure, but this seems particularly odd. Assuming it was intentional, why would the opening of Episode I reflect the opening of Episode VI (and at such an incredible level of detail, no less)? It definitely doesn’t feel like the usual, run-of-the-mill fanservice that’s so common in movies nowadays. Nor does it feel like a traditional framing device, since the beginning of Menace reflects the beginning, rather than the end, of Jedi.

So, is there something going on here? Or is this just a really strange coincidence and I’m reading too much into things?

Unfortunately, Red Letter Media’s Menace review doesn’t mention anything about the likenesses between the two sequences. The closest thing we get to an explanation is probably Stoklasa’s complaint that “Nothing in The Phantom Menace makes any sense at all. It comes off like a script written by an eight-year-old. It’s like George Lucas finished the script in one draft, like he turned it in and they decided to go with it, without anyone saying that it made no sense at all, or it was a stupid incoherent mess.” 2

However, in Red Letter Media’s review of Star Wars: Episode III—Revenge of the Sith (2005), Stoklasa does offer up two possible explanations for any and all of the similarities between the old films and the new films: “a lack of originality or a lack of vision.” 3

Over a montage showing many of the references to the original trilogy that can be found in the much-maligned prequel trilogy he says, “The new films just borrow and recycle from the original ideas, as if there’s no way to create anything new.” 4

But is this really the case?

Anne Lancashire, professor of Cinema Studies and Drama at the University of Toronto (and whose seminal writings on Star Wars form the basis for much of this essay), offers a third, perhaps more thoughtful, possibility that might help shed some light on the matter.

In her 2000 essay, “The Phantom Menace: Repetition, Variation, Integration,” she argues that with the prequels, George Lucas was creating something unique in popular film:

Not a series of narratively independent sequels and prequels (the normal mode in movie sequelization), focused on film genre conventions and/or on specific actors/roles, nor an old-fashioned serial with (merely) narratively interlocking episodes, but an epic mythological saga—full of exotic locales and monsters, like the sagas of old—consisting of at least six mutually-dependent parts interrelated in an intricately designed narrative, mythological, and metaphoric whole. 5

This means that Lucas was expanding the original trilogy into an “epic sextet, with patterns of plot and structure, cinematic allusions, and visual imagery acquiring meaning above all from [their] interrelationships.” 6 So, according to Lancashire, each film should be read in terms of its part in the larger, unified whole.

Lucas himself alluded to this in an interview following the release of Star Wars: Episode II—Attack of the Clones (2002): “Each episode has to stand on its own and have meaning on its own—except that it’s only one chapter in the book. It’s not the book. I can’t sacrifice one for the other, so I’m constantly balancing between the now and the larger picture. The now has to be engaging, but the larger picture is what’s really important.” 7

Lancashire contends that Lucas began his “carefully designed interrelationships” between the six films by deliberately basing Menace’s narrative on A New Hope’s:

Anakin Skywalker (eventual father of Luke) is [Menace’s] version of A New Hope’s Luke, going through narratively similar situations and experiences. Anakin, like Luke, is a young boy on the desert planet of Tatooine, from a “broken” family, who is suddenly given the opportunity to embark on an epic quest involving a beautiful, royal young woman in need of his help and a Jedi knight who becomes his mentor. Like Luke, Anakin accepts the opportunity and is flown through space with his mentor to face a test (for Luke, the Death Star rescue of Leia; for Anakin, a literal test before the Jedi Council). Like A New Hope, the film then ends with the boy’s special powers (including his capacity for friendship and love) permitting him to save his friends from annihilation by destroying an enemy battle station. Details of the narrative also correspond from one film to the other: the Jedi mentor’s advice to the protagonist to rely on his feelings, the death of the mentor in a light-saber duel, the association of allies with ancient sacred ruins. 8

Also, as Lancashire points out, in repeating the narrative pattern of A New Hope, Lucas deliberately repeats that film’s mythological pattern as well:

Like the plot of A New Hope, that of [Menace] takes us through the three stages of [Joseph] Campbell’s monomyth: the hero’s departure (on his quest), initiation (testing experiences), and return (the emergence from tests to achieve a final victory). This is also both the plot pattern of each of [Star Wars: Episode V—The Empire Strikes Back (1980)] and [Jedi] (with Empire’s “return” phase completed only at the start of Jedi) and, as well, the overarching pattern of the first-made trilogy as a whole (A New Hope as departure. [Empire] as initiation. [Jedi] as return). The integrating viewer can now perceive that Star Wars 1 through 6 will give us the same pattern arching over all six films, in relation to Anakin as hero: with his departure in [Menace], initiation in episodes 2 – 3, and return in 4 – 6 (beginning with his discovery of his son Luke in 4 – 5, and ending with his self-sacrificial death for Luke, and therefore resurrection, at the end of 6). 9

Repeating the patterns of plot and myth, Lancashire argues, gives the saga, among other things, “a sense of repeating, increasingly complex cycles of human experience,” within individual lives, from one generation to the next, and “within the overall movement of Anakin’s entire life from boyhood to death.” 10

In addition: “[The repeated patterns] also allow, through variations, an emotionally and intellectually complicating emphasis upon difference and change. The broad pattern of human life, from youth to maturity to death, remains constant, but individual circumstances within the pattern inevitably differ, creating different possibilities and problems.” 11

It’s also worth mentioning that the sense of repeating cycles is not only personal, but also political as the films, taken as a whole, reflect the perpetual rise and fall of democracies (the Republic) and dictatorships (the Empire).

Overall, though, Lancashire sees the repetitions as playing a significant part in the design and purpose of the films.

Now, Lucas has spoken often about the use of repetition in Star Wars. He typically puts it in a musical context: “[Star Wars] is purposely written like a piece of music, with themes that repeat themselves in different ways, and ideas that reprise from one generation to the next.” 12 However, in The Beginning, a documentary on the making of Episode 1, he instead likens the repetitions to poetry: “Instead of destroying the Death Star [like Luke], [Anakin] destroys the ship that controls the robots. It’s like poetry. Every stanza kind of rhymes with the last one.” 13

Consider Mike Stoklasa unimpressed: “That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard.” 14

Nevertheless, let’s put Stoklasa’s personal feelings aside and stick with the rhyming idea for the moment. Now, it should be fairly evident at this point that Menace and A New Hope are intricately woven together. In fact, even the episode titles themselves are connected, both thematically (menace/evil and hope/good) and structurally (article-adjective-noun).

But what about the other episodes?

Well, to take Lucas’s poetry analogy one step further, if the Star Wars films are a six-stanza poem, and each film represents one stanza, then the rhyme scheme is ABC A’B’C’. That is, Menace (A) corresponds with A New Hope (A’), Clones (B) corresponds with Empire (B’), and Sith (C) corresponds with Jedi (C’). And as mentioned elsewhere, this is clearly evidenced by comparing the final shots (or almost final, in the case of Empire) of each pair.

So, if we were to examine the other two pairs of corresponding films, we would find that the episodes in each pair are related to each other in much the same way that Menace is related to A New Hope. This, according to Lucas, is done to parallel the journeys of Luke and Anakin: “It’s very, very clear in the two trilogies that I’m putting the characters in pretty much the same situations sometimes even using the same dialogue so that the father and son go through pretty much the same experience.” 15

That’s all well and good but what about our original question: Why does the beginning of Menace reflect the beginning of Jedi? It’s even more confusing now that we know that Menace clearly corresponds to A New Hope.

Are we any closer to explaining it?

No.

Not even close.

Because here’s the thing: The “intertextual patternings,” while critical to reading the films the way Lucas intended, are actually small pieces of a much larger, more complex puzzle. And while many have unknowingly stumbled upon some of the pieces over the years, no one has discovered the underlying pattern and discussed how all of the pieces fit together and what the completed picture looks like (and possibly represents)—until now.

And it starts with a little-known ancient literary form that scholars have identified as “ring composition.”

From millennia-old Chinese writings to the epic poetry of Homer to the Bible, ring composition is a structure commonly found in ancient texts all over the globe—transcending time, culture, and geography. Social anthropologist Mary Douglas explains the technique in her book Thinking in Circles: An Essay on Ring Composition. And for starters, she writes that the form “comes in many sizes, from a few lines to a whole book.” 16

In its simplest and most popular form, it is know as “chiasmus”—a figure a speech in which key words or phrases are repeated in two successive clauses or sentences, but in reverse order. For example, John F. Kennedy’s famous line, “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” The second clause is a reversal of the first. So, the words are arranged in an ABB’A’ fashion: country(A) you(B) you(B’) country(A’). 17

A ring composition, according to Douglas, is essentially a “large-scale, blown-up version of the same structure.” 18 (It’s also commonly referred to as “chiastic structure” or “inverted parallelism.”)

Here’s how it works:

The story is organized into a sequence of elements that progress from a beginning to a well-marked midpoint. Then, the ring turns and the first sequence of elements is repeated in reverse order until the story returns to the starting point.

That means the first and last elements correspond to each other, the second and second-to-last elements correspond to each other, the third and third-to-last elements correspond to each other, and so on, creating a sort of circle or mirror image. If we assign letters to each element, the pattern is ABC C’B’A’ (similar to the JFK example above).

The correspondences between matching elements (or sections) are usually signaled by clusters of key words that appear in both items of a pair. They often indicate thematic links between the sections 19 so “one section has to be read in connection with another that is parallel because it covers similar or antithetical situations.” 20 It’s similar to the way the rhyme scheme of a poem works, but instead of rhyming sounds, the author parallels and contrasts ideas.

So, by now you’re probably wondering what any of this has to do with Star Wars?

Well, as this essay will show, the six Star Wars films together form a highly structured ring composition. The scheme is so carefully worked out by Lucas, so intricately organized, that it unifies the films with a common universal structure (or what film scholar David Bordwell might call a “new formal strategy”), creating a sense of overall balance and symmetry.

At the same time, Lucas’s use of this ancient form revises our readings of the films and the saga as a whole, and opens up new ways of thinking about Star Wars. It also allows us to gain a much greater understanding and appreciation for the films, and gives us a deeper sense of the magnitude of Lucas’s accomplishment.

Because contrary to Stoklasa’s claims that the prequels show a “lack of vision or originality” on the part of Lucas, the ring composition reveals quite the opposite. Lucas’s vision is almost startlingly ambitious and, to my knowledge, unlike anything that’s ever been attempted before in the history of cinema (proving once again that the six Star Wars films deserve far more serious critical attention than they’ve received). The word “brilliant” is often overused when discussing movies, but this is one occasion when it’s truly warranted.

The Rules of Ring Composition

Douglas provides seven rules for identifying ring compositions. She’s quick to point out, however, “they are not rules in the sense of there being something hard and fast about them. Breach carries no penalties, but insofar as they are commonly observed they are like rules. They are responses to the technical problems of coming back gracefully to the start.” 21 The rules are as follows:

1. Exposition or Prologue: “There is generally an introductory section that states the theme and introduces the main characters,” explains Douglas. “You can call it a prologue. It sets the stage, sometimes the time and the place. Usually its tone is bland and somewhat enigmatic. It tells of a dilemma that has to be faced, a command to be obeyed, or a doubt to be allayed. Above all, it is laid out so as to anticipate the mid-turn and the ending that will eventually respond to it.” 22

2. Split into two halves: The ring composition must split into two halves at the midpoint.

Says Douglas: “If the end is going to join the beginning the composition will at some point need to make a turn towards the start. The convention draws an imaginary line between the middle and the beginning, which divides the work into two halves, the first, outgoing, the second, returning.” 23

3. Parallel sections: The two halves of the ring must be arranged in parallel. According to Douglas, this is done by making separate sections that are placed opposite each other across the central dividing line (one on each side of the ring). “Each section on one side has to be matched by its corresponding pair on the other side.” 24

4. Indicators to mark individual sections: The individual sections of the ring composition must be clearly marked so the reader knows where each section starts and stops. 25

5. Central loading: Whereas modern stories are usually presented in a clear, linear fashion with the climax occurring near the end, ring compositions tend to place the climax or central crisis of the narrative in the middle (with the parts proceeding the middle moving towards it, and the parts following the middle moving away from it). “One clue that the middle has been reached,” says Douglas, “is that it uses some of the same key word clusters that were found in the exposition. As the ending also accords with the exposition, the mid-turn tends to be in concordance with them both. Then the whole piece is densely interconnected.” 26 In addition, the most important message of the work tends to be delivered at the turn or the center of the ring.

6. Rings within rings: A large ring composition may, in fact, include smaller rings. “Some rings emphasize the division into two halves by making each half a ring,” says Douglas. “A large book often contains many small rings. They may come from different sources, times, and authors. One large ring can be composed entirely from minor rings strung together in groups. This practice makes the ring form ideal for incorporating old materials, as in the Bible.” 27

7. Closure at two levels. Finally, the ending of a ring composition must join up with the beginning and make a clear closure on both a structural and thematic level. “The exposition will have been designed to correspond to the ending. When it comes the reader can recognize it as the ending that was anticipated in the exposition.” 28

Douglas contends that to read a ring composition like a conventional narrative is to misinterpret

it. 29 Instead, they are carefully designed to be read in a circular, rather than linear, fashion. And the full meaning of the text only becomes clear when the reader grasps the interplay between corresponding elements. “Writings that used to baffle and dismay unprepared readers,” she says, “when read correctly, turn out to be marvelously controlled and complex compositions.” 30

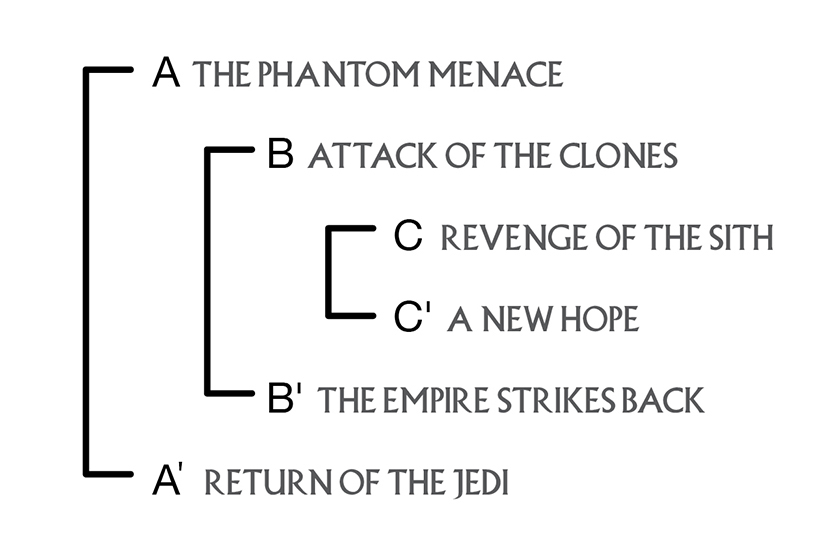

Before we plunge into the details of the Star Wars ring composition, though, it’s a good idea to see a high-level overview of how it works. So, here is the overall pattern or rhyme scheme of the Star Wars ring:

The pattern is ABC C’B’A’. Therefore, The Phantom Menace (A) corresponds to Return of the Jedi (A’); Attack of the Clones (B) corresponds to The Empire Strikes Back (B’); and Revenge of the Sith (C) corresponds to A New Hope (C’).

The pattern is ABC C’B’A’. Therefore, The Phantom Menace (A) corresponds to Return of the Jedi (A’); Attack of the Clones (B) corresponds to The Empire Strikes Back (B’); and Revenge of the Sith (C) corresponds to A New Hope (C’).

What this means is that the sequence of elements (or episodes) starts with The Phantom Menace and progresses to Revenge of the Sith, where events come to a crucial midpoint. Then, the ring turns and the first sequence (ABC) is repeated in reverse order (C’B’A’), bringing the story full circle back to the beginning.

And whereas corresponding sections in a ring composition are traditionally marked using clusters of key words, each pair of corresponding films in the Star Wars ring is meticulously matched using different aspects of cinema—including narrative structure, plot points, visuals, dialogue, themes, and music.

So, now let’s see how closely the six Star Wars films meet the above criteria. First, we’ll look at Menace as an introductory section and as a parallel episode to Jedi. After that, we’ll look at Clones as a parallel episode to Empire. Then, Sith to A New Hope. And finally, we’ll go over closing the ring, the all-important center, and the possible significance of the whole thing.

Notes:

- Mike Stoklasa, “Star Wars: The Phantom Menace Review (Part 2 of 7)” YouTube video, 9:49, April 9, 2012, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZG1AWVLnl48. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Mike Stoklasa, “Mr. Plinkett’s Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith Review” YouTube video, 1:46:19, March 12, 2014, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ABcXyZn9xjg. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Anne Lancashire, “The Phantom Menace: Repetition, Variation, Integration,” Film Criticism 24, no. 3 (March 2000): 24. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Scott Chernoff, “The Plot Thickens,” “Star Wars” Insider, July/August 2002, 58. ↩

- Lancashire, “Menace,” 26. ↩

- Ibid., 26-27. ↩

- Ibid., 27. ↩

- Ibid., 28. ↩

- Chernoff, “Plot Thickens,” 58. ↩

- George Lucas, “The Beginning: Making Episode I,” Disc 2, The Phantom Menace, DVD, directed by George Lucas (Beverly Hills, CA: Twentieth Century Fox, 2001. ↩

- Stoklasa, “Revenge of the Sith.” ↩

- George Lucas, “Audio Commentary,” Disc 1, The Phantom Menace, DVD, directed by George Lucas (Beverly Hills, CA: Twentieth Century Fox, 2001). ↩

- Mary Douglas, Thinking in Circles: An Essay on Ring Composition, Terry Lecture Series, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 2. ↩

- For the purposes of this essay, I do not differentiate between chiasmus and antimetabole. ↩

- Douglas, Thinking in Circles, 2. ↩

- Ibid., 33-34. ↩

- Ibid., 6. ↩

- Ibid., 35. ↩

- Ibid., 36. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 37. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 37-38. ↩

- Ibid., preface, x. ↩

- Ibid., 1. ↩